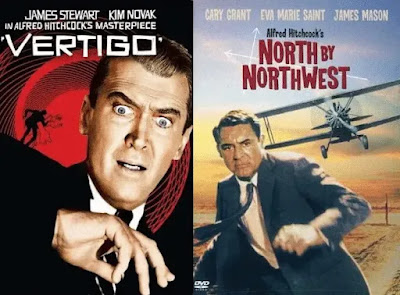

- Everybody pretty much agrees that North by Northwest is a perfectly constructed film. It fits together better than any other Hitchcock movie. And, yet, you say Vertigo is considered to be “greater” by almost every critic. How can Vertigo, which is really messy, be better than North by Northwest, which is perfect?

But depth is found in holes. A few unanswered questions and unresolved emotions are necessary to really have a profound effect on a viewer. Right at the beginning of Vertigo, we abruptly cut from Jimmy Stewart, dangling from a building in terror, with no rescue in sight to several months later, as he talks with a friend about leaving the police force. We can figure out what happened in between, but because we never see the rescue, we’re left with the unresolved disturbance of his emotional reaction.

Similarly, I mentioned earlier that Madeleine’s disappearance from the hotel room is never explained. Again, we can hazard guesses, but the refusal to tidy up this loose end gnaws at us on a subconscious level.

These aren’t really plot holes; they’re just holes, gaps in the story, and that’s what makes Vertigo a greater film than North by Northwest. Great art shouldn’t be entirely satisfying. It has to disquiet us a little—and have a few holes for us to get stuck in.

Rulebook Casefile: The Value of the Untidy Gaps in Blue Velvet

So how do you chop four hours down to two? Well, there are a lot of candidates for cutting here: odd cappers on scenes that feel creepy and unmotivated (“You know the chicken walk?”), long silences while Jeffrey watches things, the strange visit to Dean Stockwell’s house, generic montages of small town life, etc… The natural impulse would be to cut out everything but plot essentials until you have a lean, mean two-hour movie that “really moves”, as the critics say.

But Lynch could tell the difference between the baby and the bathwater. He left the idiosyncrasies in and chopped huge chunks of the plot out. The result is that we never make much sense of what’s really going on, but that’s fine. Lynch knows that untidiness can increase the meaning and power of a movie.

He could have said “Wait, if we don’t see them finding the second ear in the sink, then won’t it be confusing that Don is missing two ears when they find his body at the end?” And the answer is of course, “yes,” but it’s the right sort of gap: one we can fill in on our own if we care to (presumably the same people cut the second one off too, right?) but we don’t need to. It’s just another unexplained detail that make the world seem bigger than the movie, which is something the audience likes.

Of course, even with the plot sliced way down, there was still more to cut, so Lynch’s decision to cut out many of Jeffrey’s early scenes was even more daring. We originally met Jeffrey at college, watching from afar as a girl is almost date-raped, and only stopping it when someone else approaches the scene. This clearly sets up his longstanding problem. Then there were a lot more scenes when he first arrives in town that showed his frustration with his mom and aunt, including one where his mom tells him that they won’t be able to afford college for him anymore, causing him to worry that there will be no outlet for his darker impulses at home.

As I wrote about before, sometimes you have to write deleted scenes. Without those scenes on the page, the character would have seemed much less compelling until almost halfway in, but Lynch discovered he could cut them from the final movie because his amazing star, Kyle McLaughlin, managed to convey all of that deviance and frustration beneath the placid surface of his creepy/charming face. Just the curious way he looks at that ear basically tells us everything we need to know.

The Problem: This should also be off-putting, denying the audience a chance to decide for ourselves what everything means in the end. And by tying off all of the loose plot threads, we have less to think about afterwards.

Does the Movie Get Away With It? Somewhat, but it’s more problematic than the opening montage. Let’s start with the montage of what happens to all of the other characters. On the one hand, it’s delightful to see Gale and Evelle go back to prison by climbing back into the mudhole they climbed out of, but surely there was no need to show brother-in-law Glen getting his eventual comeuppance after telling a Polish joke to a Polish cop?

As for Hi’s summation of what happens to himself and Ed, the ending tries a little too hard to be satisfying by having it both ways:

- First we get the “real consequences” version, in which the couple, still childless, content themselves to send anonymous gifts to Nathan Arizona, Jr, every year, and live vicariously through his accomplishments.

- But then we get another vague ending tacked onto that one, implying that Hi and Ed somehow did get to raise kids and have a large family of their own someday.

The 40 Year Old Virgin | YES, the other guys’ relationships remain vague. |

Alien | YES. Very much so. We know very little at the end about what was really going on. If only someone would do a prequel! |

An Education | YES. What was his plan? Bigamy? A phony marriage? Leave his wife? We never know. |

The Babadook | YES. Very much so. The ending is very tantalizing and bizarre. |

Blazing Saddles | YES. everything is vague at the end. |

Blue Velvet | YES. huge questions are left unanswered. |

The Bourne Identity | NO. It’s fairly tidy, but that’s fine. |

Bridesmaids | YES. Somewhat. The romance certainly isn’t tied up with a bow. |

Casablanca | YES. we don’t find out the fate of the other couple trying to get free, for example. |

Chinatown | YES. Very much so. If you go back and think about it, little of it makes sense, but the audience doesn’t care. |

Donnie Brasco | YES. |

Do the Right Thing | YES. Will Mookie comes back to Tina, etc. |

The Farewell | YES. It’s very untidy. We never find out if Billi finds a way to make it in NYC, etc. |

The Fighter | YES. Very much so. The events are very messy. |

Frozen | YES. We never find out the source of the powers, etc. |

The Fugitive | Not really. We even see that Cosmo is okay. It’s a pretty tidy ending. |

Get Out | YES. Lots of them. Will he be able to explain any of this to the cops? What about all the other victims? (Of course, there are even more loose ends in Peele’s next movie.) |

Groundhog Day | YES. Very much so. What caused this? We’ll never know. |

How to Train Your Dragon | NO. Hmm… It’s pretty tidy. |

In a Lonely Place | YES. we never find out how and why the murder happened. |

Iron Man | YES. In the truly terrible deleted scenes, everything is explained in much more details, and as a result the story feels leaden and meaningless. |

Lady Bird | YES. She still hasn’t found love. She still hasn’t told anyone the truth about being from Sacramento. |

Raising Arizona | NO. It’s fairly tidy, using lots of voiceover to explain lots of little things, like what happened to the brother-in-law, etc. |

Rushmore | YES. everyone is there for the finale, but their stories don’t wrap up neatly. |

Selma | YES. The tension with SNCC and with Coretta is mostly left unresolved. It would be great to see a sequel. |

The Shining | YES. We don’t understand the final shot, for instance. |

Sideways | YES. It’s not clear what will happen when he shows up at her door. |

The Silence of the Lambs | YES. Lecter remains free, and we never fully understand the mechanics of his escape. |

Star Wars | YES. Vader lives, the empire continues, and Jabba’s debt is still looming over Han. |

Sunset Boulevard | YES. It’s fairly tidy, but one big question is never answered, though: Did Joe decide to leave Norma before or after he sent Betty away? |

4 comments:

"But depth is found in holes." This is such a great observation. While I'm completely fascinated by how plot and structure work, I've always preferred stories that are surreal and bewildering. Like a weird dream that doesn't make sense and yet has a huge emotional impact. I'm currently focused on short story writing where there simply isn't the space to hit all these points. Maybe you could, but it would feel incredibly forced. I'm still playing with how to use the checklist for this purpose—which items can be left out or glossed over and still have a story that works well on some level. I try to jot something down for each question, even if I never intend it to surface in the story. But it might show up as some glimmer, subconscious even, that adds richness to the piece.

I'd love to see a bare bones version of the checklist. Like what points have to be hit in any story, in your opinion.

Really enjoying your book, by the way. So direct and practical. Love it. Thank you.

So glad you like the book and blog posts, Robin! I've never done a deep dive into short stories to figure out what beats they hit, and "short story" means so many different things, from Saunders to Carver to Bradbury to Woolrich, that I doubt I could do it. I would suggest you analyze your favorites and figure out how many of these 122 questions they can answer. It's certainly going to be less than 122!

The vast scope of marketing studies often leaves students confused about how to approach assignments. From global branding strategies to digital consumer trends, the workload can be extensive. That’s why many turn to a Marketing Assignment Writing Service for reliable academic assistance. These services are staffed with professionals who have in-depth knowledge of theories and practical applications. By choosing expert guidance, students receive original, well-referenced, and structured assignments that meet academic standards. Beyond grades, these assignments also help in understanding key concepts better, making it easier to apply them in exams and future careers. For students struggling to manage multiple responsibilities, this becomes a practical solution.

University life in the UK is exciting but equally demanding when it comes to academics. Students often face pressure to meet strict deadlines while maintaining quality in their assignments. That’s where Affordable University Assignment Help UK becomes valuable. It offers professional writing assistance across multiple subjects and formats while keeping student budgets in mind. The writers take special care to create content that is plagiarism-free and tailored to individual requirements. What makes the service stand out is its ability to deliver complex assignments on time without compromising standards. Many students appreciate the customer support, which is responsive and supportive throughout the process. Overall, it’s an excellent choice for learners who need affordable yet dependable academic help.

Post a Comment