Podcast

Thursday, December 07, 2023

Episode 45: Specific vs. Generic (Or is it Factual vs. Archetypal?)

Wednesday, December 06, 2023

The Expanded Ultimate Story Checklist is Complete!

For each item in the Ultimate Story Checklist, I’ve created a new post with the text from the book, followed by every Rulebook Casefile and every Straying From the Party Line post I did on that topic, followed by a table with how each of the thirty movies I analyzed answered that question. Now that they’re all up, I’ve relinked the Expanded Checklist in the sidebar to link to the expanded posts. I left the original Checklist in there too, which links to the original posts I based the book on, and, crucially, has all the comments those posts attracted, which are well worth reading.

So what’s next? I’ll finish 37 Days of Shakespeare soon. That was going to be my New Year’s Resolution, but it may get delayed, we’ll see.

Tuesday, December 05, 2023

The Expanded Ultimate Story Checklist: Do the characters refuse or fail to synthesize the meaning of the story?

Modern Family can be an entertaining sitcom—as long as you turn it off two minutes early. At the end of each episode, you have to watch a member of the family come onscreen, look right at you, and point out how all three of that week’s storylines were really about the same big theme and how glad that person is to have learned so much. Any meaning the episode may have generated is quickly slaughtered by this clumsy exegesis.

Compare this to any of the far-superior, documentary-style sitcoms this show mimics, especially the American version of The Office. Boss Michael Scott frequently appears at the end to sum up what meaning has been created by that week’s episode. But he gets it all spectacularly wrong and forces us to do the work.

You need to have the courage to let your audience draw their own meaning, even if that means they might not “get it,” or they might even come to the opposite conclusion you intended.

What were Shakespeare’s politics? In Julius Caesar, did he agree with Brutus or Marc Antony? Does he side with Prince Hal or Falstaff in Henry IV? No one knows. His plays are filled with huge ideological conflicts but few definitive statements. He gives us a thesis and antithesis and leaves the synthesis to us. That’s why he’s immortal.

This was true in Nick Hornby’s script as well, but somewhat less so. Director Lone Scherfig is extremely faithful to the script overall, but she cuts several exchanges out of the last part of the script, and replaces the last page entirely. These judicious cuts made the movie much better, and exemplified the importance of not allowing the characters to process the theme.

In the finished film, we end with Jenny, at Oxford, happily riding a bicycle through campus with a boy she seems to be dating, as we hear a voiceover (for the first time in the movie), saying that she tried to forget the whole thing, and one day, when a boy asked her to go to Paris with him, she said yes... “as if I’d never been.” Fade to black.

On the last page of the original script, we also have Jenny bicycling through Oxford, but then, one day...

This is way too much closure. What’s so great about the final onscreen ending is that it’s haunting. She never expunges the ghost of David, so he hovers over her whole life. She can pretend that it never happened, but she’ll always know better.

Director Lone Scherfig knew she had a brilliant script on her hands...but she also knew that the last page blew it, and a better last page would make it a classic. She kept pushing until she found the last page the movie needed.

The 40 Year Old Virgin | YES. He never says what he learned. |

Alien | YES. She doesn’t say anything about the evils of corporate sovereignty in her final recording. |

An Education | YES. The original script contained much more recriminations in the third act, but in the finished film, most of those questions land in the viewer’s lap, which is better. |

The Babadook | YES. Her reversible behavior is very subtle. |

Blazing Saddles | YES. |

Blue Velvet | YES. they never talk about what it all means. |

The Bourne Identity | YES. he and Marie don’t discuss it at the end. |

Bridesmaids | YES. There is no analysis of what she’s learned after the wedding. |

Casablanca | Pretty much. He tries to say what it all means, but that’s just to get her on the plane, he hasn’t really processed the pain yet. |

Chinatown | YES. Very much so. He chooses to “forget about it” |

Donnie Brasco | YES. Donnie literally doesn’t speak again after Lefty is killed. |

Do the Right Thing | YES. They do discuss it, but they don’t kill the meaning or settle the dilemma as they do so. |

The Farewell | YES. |

The Fighter | NO. the epilogue hits it pretty squarely on the head, but that’s fine. It’s a sports movie. |

Frozen | YES. There’s not a lot of talk about what it all means. |

The Fugitive | YES. They just barely do it, and that’s fine. Gerard admits that he did come to care, this one time, but he laughs it off and says “Don’t tell anybody.” There’s no serious rapprochement. |

Get Out | YES. Chris barely speaks in the final third of the movie and won’t talk about what happened to him when Rod rescues him. |

Groundhog Day | YES. He doesn’t go back and figure out what was different about that last day. |

How to Train Your Dragon | NO. By knocking Hiccup out for the denouement, we skip the actual rapprochement between the Vikings and the dragons, but there’s still a lot of talk about what it all means. |

In a Lonely Place | YES. He synthesizes it in a pat way, but because we saw him coin that phrase before, we suspect that he is only pretending to feel the impact, or that he’s summoned up so many canned feelings for Hollywood that he can’t summon up any raw, authentic feelings anymore. |

Iron Man | YES. Stane isn’t mentioned again after he’s killed. |

Lady Bird | NO. she basically synthesizes it. |

Raising Arizona | NO. Nope, he does a lot of synthesizing, at the end and throughout. Even when he doubts his conclusion (about Reagan, for instance) we don’t. |

Rushmore | YES. Max has learned a lot, but he doesn’t want to talk about it much. |

Selma | Nope. Both King and Johnson give big speeches summarizing the meaning. |

The Shining | YES. the epilogue was cut. There is no attempt to process that we see. Danny doesn’t even speak after the finale begins. |

Sideways | YES. We never hear the final conversation. He doesn’t say what the kid’s essay means to him, etc. |

The Silence of the Lambs | YES. Very much so. We never see them second-guess the value of working with Lecter. |

Star Wars | YES. The finale is wordless. |

Sunset Boulevard | NO. he returns from the dead to spell it out for us. Wilder was not the type to leave anything unsaid. |

Monday, December 04, 2023

The Expanded Ultimate Story Checklist: In the end, is the plot not entirely tidy?

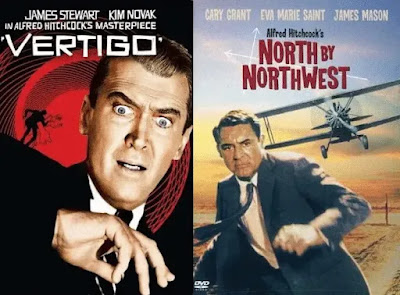

- Everybody pretty much agrees that North by Northwest is a perfectly constructed film. It fits together better than any other Hitchcock movie. And, yet, you say Vertigo is considered to be “greater” by almost every critic. How can Vertigo, which is really messy, be better than North by Northwest, which is perfect?

But depth is found in holes. A few unanswered questions and unresolved emotions are necessary to really have a profound effect on a viewer. Right at the beginning of Vertigo, we abruptly cut from Jimmy Stewart, dangling from a building in terror, with no rescue in sight to several months later, as he talks with a friend about leaving the police force. We can figure out what happened in between, but because we never see the rescue, we’re left with the unresolved disturbance of his emotional reaction.

Similarly, I mentioned earlier that Madeleine’s disappearance from the hotel room is never explained. Again, we can hazard guesses, but the refusal to tidy up this loose end gnaws at us on a subconscious level.

These aren’t really plot holes; they’re just holes, gaps in the story, and that’s what makes Vertigo a greater film than North by Northwest. Great art shouldn’t be entirely satisfying. It has to disquiet us a little—and have a few holes for us to get stuck in.

Rulebook Casefile: The Value of the Untidy Gaps in Blue Velvet

So how do you chop four hours down to two? Well, there are a lot of candidates for cutting here: odd cappers on scenes that feel creepy and unmotivated (“You know the chicken walk?”), long silences while Jeffrey watches things, the strange visit to Dean Stockwell’s house, generic montages of small town life, etc… The natural impulse would be to cut out everything but plot essentials until you have a lean, mean two-hour movie that “really moves”, as the critics say.

But Lynch could tell the difference between the baby and the bathwater. He left the idiosyncrasies in and chopped huge chunks of the plot out. The result is that we never make much sense of what’s really going on, but that’s fine. Lynch knows that untidiness can increase the meaning and power of a movie.

He could have said “Wait, if we don’t see them finding the second ear in the sink, then won’t it be confusing that Don is missing two ears when they find his body at the end?” And the answer is of course, “yes,” but it’s the right sort of gap: one we can fill in on our own if we care to (presumably the same people cut the second one off too, right?) but we don’t need to. It’s just another unexplained detail that make the world seem bigger than the movie, which is something the audience likes.

Of course, even with the plot sliced way down, there was still more to cut, so Lynch’s decision to cut out many of Jeffrey’s early scenes was even more daring. We originally met Jeffrey at college, watching from afar as a girl is almost date-raped, and only stopping it when someone else approaches the scene. This clearly sets up his longstanding problem. Then there were a lot more scenes when he first arrives in town that showed his frustration with his mom and aunt, including one where his mom tells him that they won’t be able to afford college for him anymore, causing him to worry that there will be no outlet for his darker impulses at home.

As I wrote about before, sometimes you have to write deleted scenes. Without those scenes on the page, the character would have seemed much less compelling until almost halfway in, but Lynch discovered he could cut them from the final movie because his amazing star, Kyle McLaughlin, managed to convey all of that deviance and frustration beneath the placid surface of his creepy/charming face. Just the curious way he looks at that ear basically tells us everything we need to know.

The Problem: This should also be off-putting, denying the audience a chance to decide for ourselves what everything means in the end. And by tying off all of the loose plot threads, we have less to think about afterwards.

Does the Movie Get Away With It? Somewhat, but it’s more problematic than the opening montage. Let’s start with the montage of what happens to all of the other characters. On the one hand, it’s delightful to see Gale and Evelle go back to prison by climbing back into the mudhole they climbed out of, but surely there was no need to show brother-in-law Glen getting his eventual comeuppance after telling a Polish joke to a Polish cop?

As for Hi’s summation of what happens to himself and Ed, the ending tries a little too hard to be satisfying by having it both ways:

- First we get the “real consequences” version, in which the couple, still childless, content themselves to send anonymous gifts to Nathan Arizona, Jr, every year, and live vicariously through his accomplishments.

- But then we get another vague ending tacked onto that one, implying that Hi and Ed somehow did get to raise kids and have a large family of their own someday.

The 40 Year Old Virgin | YES, the other guys’ relationships remain vague. |

Alien | YES. Very much so. We know very little at the end about what was really going on. If only someone would do a prequel! |

An Education | YES. What was his plan? Bigamy? A phony marriage? Leave his wife? We never know. |

The Babadook | YES. Very much so. The ending is very tantalizing and bizarre. |

Blazing Saddles | YES. everything is vague at the end. |

Blue Velvet | YES. huge questions are left unanswered. |

The Bourne Identity | NO. It’s fairly tidy, but that’s fine. |

Bridesmaids | YES. Somewhat. The romance certainly isn’t tied up with a bow. |

Casablanca | YES. we don’t find out the fate of the other couple trying to get free, for example. |

Chinatown | YES. Very much so. If you go back and think about it, little of it makes sense, but the audience doesn’t care. |

Donnie Brasco | YES. |

Do the Right Thing | YES. Will Mookie comes back to Tina, etc. |

The Farewell | YES. It’s very untidy. We never find out if Billi finds a way to make it in NYC, etc. |

The Fighter | YES. Very much so. The events are very messy. |

Frozen | YES. We never find out the source of the powers, etc. |

The Fugitive | Not really. We even see that Cosmo is okay. It’s a pretty tidy ending. |

Get Out | YES. Lots of them. Will he be able to explain any of this to the cops? What about all the other victims? (Of course, there are even more loose ends in Peele’s next movie.) |

Groundhog Day | YES. Very much so. What caused this? We’ll never know. |

How to Train Your Dragon | NO. Hmm… It’s pretty tidy. |

In a Lonely Place | YES. we never find out how and why the murder happened. |

Iron Man | YES. In the truly terrible deleted scenes, everything is explained in much more details, and as a result the story feels leaden and meaningless. |

Lady Bird | YES. She still hasn’t found love. She still hasn’t told anyone the truth about being from Sacramento. |

Raising Arizona | NO. It’s fairly tidy, using lots of voiceover to explain lots of little things, like what happened to the brother-in-law, etc. |

Rushmore | YES. everyone is there for the finale, but their stories don’t wrap up neatly. |

Selma | YES. The tension with SNCC and with Coretta is mostly left unresolved. It would be great to see a sequel. |

The Shining | YES. We don’t understand the final shot, for instance. |

Sideways | YES. It’s not clear what will happen when he shows up at her door. |

The Silence of the Lambs | YES. Lecter remains free, and we never fully understand the mechanics of his escape. |

Star Wars | YES. Vader lives, the empire continues, and Jabba’s debt is still looming over Han. |

Sunset Boulevard | YES. It’s fairly tidy, but one big question is never answered, though: Did Joe decide to leave Norma before or after he sent Betty away? |

Friday, December 01, 2023

The Expanded Ultimate Story Checklist: Does the story’s outcome ironically contrast with the initial goal?

In chapter three, we explored why these story concepts are ironic. Now let’s jump to the ending to see their ironic final outcomes:

- Casablanca: Rick gets Ilsa back only so he can send her away.

- Beloved: Sethe still thinks her daughter’s vengeful ghost was “my best thing.”

- Silence of the Lambs: One killer is stopped, but the worse killer gets away in the process.

- Groundhog Day: Phil finally figures out how to get out of the town he hates by deciding he wants to stay there forever.

- Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone: The most scared teacher turns out to be most useful to the villain, rather than the mean teacher. Then Harry and his friends win the house cup by breaking all the rules.

- Sideways: Miles discovers the way to get the girl is to have the courage to do nothing. He finds the book that failed to earn him the love of the world has ironically done its job after all, because it’s moved the one heart he really needed to move.

- Iron Man: Tony’s own business partner turns out to be the villain.

- An Education: At Oxford, Jenny gets the education she originally wanted, but she has to pretend she hasn’t already received a far more worldly education.

It’s ironic that Indiana’s efforts have the opposite effect of his intentions, but even more ironically, the audience realizes this forgotten bureaucratic warehouse is probably the safest place possible for this dangerous artifact. The audience has seen Indiana’s goal come to naught at the last possible second—and they love it. They actually enjoy a good ironic reversal more than a straightforward payoff.

We don’t want to live in a clockwork universe, and we don’t want clockwork stories. We don’t want to watch authors plug numbers into a machine, pull the big lever, and get the expected result. We want irony because it’s surprising, because it’s clever, and, more than anything, because it’s realistic. There are no straight lines in nature, and we don’t want any in our stories, either. We love to see our heroes get what they want in the end—as long as they don’t get it in quite the way they wanted.

But rather than leaving audiences disappointed, this was a huge aspect of the film’s success:

- It solves the Collateral problem: “This guy framed me for a killing, so I’ll track him down and kill him, and that’ll clear my name!” Um, no, that’s not how that works (to be fair, this goes back Hitchcock, in moves like Saboteur.)

- It elevates the movie morally. The audience can’t help feel dirtied by the standard logic of “he’s a killer so let’s kill him!” There’s a reason that this is one of the only thrillers nominated for best picture: nobody’s embarrassed to say they like it.

- It ties in nicely with the movie’s ironic final outcome:

As we discussed last time, it should be frustrating to us that Kimble frequently sabotages his quest, but this turns out to be exactly the right thing to do: If he’s not going to kill the villains, then what can he do with them? Make a citizen’s arrest? No, he has to win the lawmen back to his side, and ironically, he can only do so by sabotaging his cause over and over again in the name of compassion.

Every time Kimble sabotages his cause, he’s bringing about the only truly-satisfactory outcome: winning Gerard over, and reuniting law and justice. We’ll talk more about that thematic dilemma next time…

The 40 Year Old Virgin | YES, he finds sex but only by marrying a grandmother. |

Alien | YES. they kill the object of their rescue mission, the most loyal one blows up the ship. |

An Education | YES. The education she tried to reject actually leads her back to the life of sophistication she wanted, but she has to pretend she hasn’t already had it. |

The Babadook | YES. she’s the monster at the end of the book. |

Blazing Saddles | YES. He saves the town instead of dooming it. The townspeople beg him to stay instead of forcing him out. |

Blue Velvet | YES. he defeats evil by absorbing it |

The Bourne Identity | YES. Liman says that his model was The Wizard of Oz: he’s trying to get home, but he’s home the whole time, because Marie turns out to be his home. |

Bridesmaids | YES. Helen helps Annie see that she’s the problem, rather than vice versa. Her archenemy helps her get her guy. |

Casablanca | YES. Very much so: he gets her back only so that he can send her away. |

Chinatown | YES, the heroes get the opposite of what they want. |

Donnie Brasco | YES. he feels worse about betraying his fake family than his real family. |

Do the Right Thing | YES. Mookie just wanted to get paid, but he destroys his job instead. |

The Farewell | YES. She doesn’t achieve her original goal of telling the truth and decides it was better not to. |

The Fighter | YES. Very much so. What starts out as a story about breaking free of your rotten family becomes a story about taking strength from your rotten family. |

Frozen | YES. Elsa’s powers are embraced. |

The Fugitive | YES. The fugitive and the marshal work together. |

Get Out | YES. The in-laws love him, after all. |

Groundhog Day | YES. He finally figures out how to get out of there: by wanting to stay. |

How to Train Your Dragon | YES. Very much so. The opening dragon attack is paralleled by the final peaceful shots of dragons flying through the village. |

In a Lonely Place | YES. he clears his name but loses the girl anyway. |

Iron Man | YES. He earns the right to be a super-hero and then immediately breaks the first rule. |

Lady Bird | YES. She seeks out the comforts of home (church and calling her mom) in New York. |

Raising Arizona | YES. they are pushed apart by stealing the baby and brought back together by returning it. |

Rushmore | YES. He tries to hook up Cross with Blume instead of trying to break them up. |

Selma | Yes and no. For Johnson certainly. For King, he tells Coretta at the beginning that his whole goal is to wrap this up and settle down to life in a college town with “maybe an occassional speaking engagement,” and he certainly doesn’t achieve that. But it could be that King was lying to Coretta about wanting to settle down, in which case, he unironically achieves exactly his initial goal. (Of course the fact that Johnson hurts his marriage is certainly not something he planned on) |

The Shining | YES. they save their family by killing the dad. |

Sideways | YES. Miles finds that the way to get the girl is the have the courage to do nothing, waiting for her to re-approach instead of drunk dialing her. |

The Silence of the Lambs | YES. They catch one only to lose another. |

Star Wars | YES. He defeats the bad guys using the technology he learned at home, not by acting like the other pilots. |

Sunset Boulevard | YES. he gets his pool, she gets her return to the screen, and Max even gets to direct again, but all in the most ironic ways possible. |